Ian Barnard | Chapman University

Editors’ note: Barnard’s essay is part of the collaboration, “Remembering bell hooks: Teaching/Learning/Thinking/Writing in Desperate Times”.

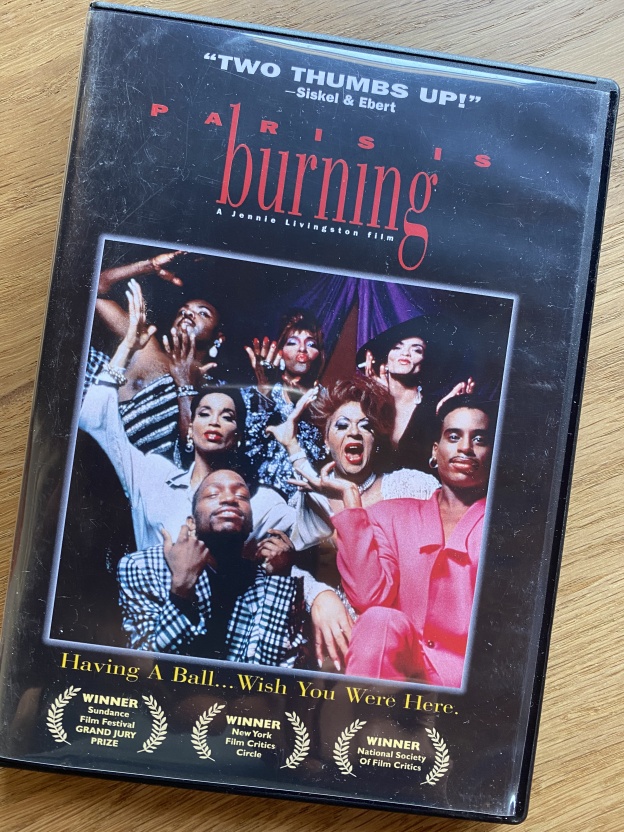

My collaborators and I are remembering and celebrating bell hooks from a variety of subject positions, perspectives, and life practices (students, scholars, writers, activists) and the intrication of these position and practices (indeed, Montéz is my former graduate student; Sophia is Aneil’s former undergraduate student). My contribution to this cluster focuses on bell hooks’ pivotal impact on my work as a teacher. hooks, of course, in addition to having taught in various capacities and at many institutions for 40 years, wrote multiple books that insisted on the transformative importance of teaching. In my almost 40 years of college teaching at seven different universities, bell hooks is the author I have assigned in my classes more than any other (she is also the scholar I have cited most often in my research, but that’s a topic for another blog post…), from her early work on Madonna, to her essays on films like The Attendant and Paris is Burning, her writings on pedagogy, and her more recent criticism of Beyoncé that Montéz wrote about so poignantly. Even when I disagree with hooks (and I often do), her work has always provoked rich class discussion like no other critic my students and I have engaged with, and has often propelled critical thinking and scholarly passion in students who might otherwise not feel particularly committed to course materials.

When I was a graduate student in the early 1990s, I saw bell hooks presenting her infamous argument about Madonna’s racism at the San Diego Museum of Contemporary Art. All hell broke loose during the Q and A after hooks’ riveting presentation, when a self-identified Italian audience member defended Madonna on the grounds that as an Italian-American, Madonna was a woman of color, and thus bell hooks needed to reconsider Madonna’s racial representations. hooks was having none of it. When I later taught hooks’ Madonna essays to my undergraduate composition students, many were equally outraged. But hooks got us talking about race in Madonna’s work, something that no cultural critic at the time had really been addressing. That’s the thing: hooks has often been the first or only scholar to bring previously absent but crucial perspectives to bear on a topic or film we are working with, a point that Montéz alluded to when recounting her initial hurt reaction to hooks’ critique of Beyoncé.

When I first started teaching hooks, non-Black students in my classes would often complain about her “angry” tone (my students then were not quite as politically aware and as generous as my wonderful Generation Z students are today). When my students complained about hooks being “angry,” I asked them if they thought they would have the same reaction to a similarly written text by a white man, a question that would inevitably lead to discussions of the trope of the “angry Black woman” (see Boylorn; Gallagher and Germain), and how it is used to discount the voices and view of Black women. These kinds of reflections helped us to be more reflexive about our responses to hooks and they segued into important discussions of the politics of tone and propriety in general, especially of tone policing in the composition classroom. Doubly especially tone policing in the writing of first-year composition students and of the ways in which emotion gets pathologized in academia (and in composition) and of productive uses of anger in writing. My students are so used to being told that their writing should be dispassionate and “objective” (and they’re still being told not to use “I”) that they’ve often internalized these values and use them to judge other writers (see Barnard). Questioning these values became an important part of the critical thinking that hooks propelled in my classrooms.

hooks herself has pointedly addressed these issues around tone politics and race. In her book Teaching Critical Thinking, hooks discloses that early in her teaching career students complained that she was “racist” because she “called attention to racial identity,” and how her “critiques of systems of domination risked being viewed as expressions of personal anger” (99). “Again and again,” she says, “black female professors come together and discuss among ourselves ways to challenge all students, but particularly those white students who wrongly project onto us that we are angry or mean” (99). Here hooks not only alludes to the prevalence of the “angry Black woman” stereotype, but also to an understanding that students’ projection of her anger is often a displacement of uncomfortable subject matter onto the supposedly formalist matter of tone, a defensive reaction to her work because of the way it tackles questions of power and discrimination, especially racism, head on. Instead of registering their discomfort with hooks’ exposés of racism, students complained about her tone. The fact that my students felt justified in pathologizing hooks’ “anger” is also an indictment of the misplaced and ideologically-heavy value that composition pedagogy has invested in the corrupt (and racist) notions of objectivity, civility, moderation, and scholarly distance that I discuss in the previous paragraph. In addition, I think students were often so overwrought by hooks’ subject matter that they missed the humor in her work. I certainly thought she called Beyoncé a terrorist with a twinkle in her eye, but many earnest Beyoncé fans (including Angela Davis and my students) seemed to miss hooks’ deliberate sense of provocation when they attacked hooks for daring to criticize their beloved Beyoncé. And when my students responded with outrage to hooks’ assertion about Madonna’s film Truth or Dare that “Madonna must have searched long and hard to find a black female dancer that was not a good dancer” (Black Looks 163), I protested that they were missing hooks’ playfulness, that she was having fun with them—hooks even prefaces that comment by noting that it was made when she and other black folks were “joking about the film.” But that’s the problem with the trope of the angry Black woman—you can only be one thing: mad as hell.

My students’ negative response to hooks was also a resistance to Black female authority in the sense that my students saw the texts they read in class as authoritative. As the large body of scholarship on student perceptions of women teachers and teachers of color demonstrates, it was doubtless easier for me as a white professor to intervene into these types of student responses to hooks, since my students—especially the white students—felt compelled to engage issues of tone and racist stereotypes when I challenged their resistance to hooks. If I were a professor of color, they may been tempted to imagine their professor in the same terms that they had framed hooks, seeing their professor as “biased” and too invested in the topic to teach it effectively. I think this understanding of how much our racialized identities shape teaching and learning also nuances the places we authors find hooks and the routes through which we come to hooks in this cluster of blog posts, as, for example, each of our differently racialized and gendered subject positions give us diverse kinds of access to and affordances with hooks’ work.

Now even though my non-Black students often responded negatively or defensively to hooks’ challenging analysis of the popular culture texts that they held dear, as I have suggested, hooks’ interventions nevertheless often served as turning points in critical classroom considerations of these texts. Those turning points prove to be the continuity of my experience with hooks across the decades. They bring me to the present, to bell hooks and critical thinking, that much touted, maligned, misused, and overused university talking and selling point that has been on my mind quite a bit since I taught a “First Year Foundations” (also called “First Year Focus”) course last year that is the only required course at my institution, and whose only goal, as its director repeatedly emphasized to faculty teaching the course last Fall, was to inculcate “critical thinking” habits into its 1717 strong cohort of fresh-out-of-high-school new university students. I explained to my students that semester that I define critical thinking as thinking (and writing and visual text and oral discourse) that resists easy answers and that actively seeks nuance and complexity. Look for complications, I encouraged my students. For many of them, this advice was counter-intuitive and counter to what they’d been taught before.

In her book Teaching Critical Thinking, hooks writes about having “wanted to become a teacher who would help students become self-directed learners” (3) and characterizes critical thinking as a way of approaching ideas that eschews superficial truths that are most obviously visible (9). For students, not opting for received wisdom first, or, at least, imagining nuancing, interrogating, and complicating received wisdom, is a way of learning about learning, and, more parochially, learning how to develop work that hopefully is valued in the university and beyond. hooks’ early book Outlaw Culture: Resisting Representations offers a model of cultural criticism in this vein, and, indeed, some of us used this text as a framework for composition courses when the book came out almost 30 years ago. In it, hooks unexpectedly dialogues with Ice Cube, attacks Spike Lee, and was the first to offer a critical race analysis of The Crying Game. And that’s just 2 ½ of the 20 chapters! hooks’ unexpected insights continue to provoke and stimulate my students 30 years later. Last year I assigned hooks’ essays on Black gay British filmmaker Isaac Julien’s experimental short film The Attendant and white lesbian US filmmaker Jennie Livingston’s cult hit documentary Paris is Burning in my Queer Cinema-themed First Year Foundations class. In each case, hooks’ argument electrified our class discussion—almost every one of the 27-member class had something to say. hooks got the students to think about things they might never have otherwise (the absence of female desire in The Attendant; Livingston’s failure to reflect on her own subjectivity in Paris is Burning), and to question their rather uncritical celebrations of what they had assumed were dissident works of art. And even where students disagreed with hooks, they ended up complicating their own readings of the films and of the larger social and political issues they implicated, and incorporating their new perspectives, or their interchanges with hooks into their own work. Students commented excitedly after our class discussions of hooks’ work how rich and stimulating they had found the discussions. In Teaching Critical Thinking, hooks herself notes how she remembered class discussions rather than lectures from her own education; she also writes about the capacity to be awed and excited by ideas (188), and this is exactly the capacity that her work evokes in my students.

Because hooks’ work is so accessible, students also become excited by the idea that they can disagree with published scholarly work—this is one of the ways of engaging with sources promoted in Cathy Birkenstein and Gerald Graff’s best-selling text book They Say/I Say: The Moves that Matter in Academic Writing, but I find that my undergraduate students are often intimidated by sources, assume that something must be “right” if it has been published by a reputable scholar, and fall into the default mode of using sources to “support” their points, never imagining that they could critique these sources. hooks helps them learn how to really engage with sources. hooks also insists that critical thinking is an interactive process that demands participation of students and teacher alike (Teaching Critical Thinking 9), and certainly these class discussions have challenged my own ideas and I’ve frequently changed or qualified my own opinions as a result of listening to my students or reading hooks or mediating my students’ reading of hooks. Indeed, student reflections on Paris is Burning got me to think about aspects of the film I hadn’t considered before. Contrarily, I’ve often found myself defending hooks’ positions in class, even though I had not been persuaded by these positions when I first read them, in my quest to urge my students to complicate their thinking.

At the end of my First Year Foundations course last Fall, I asked my students to reflect on the extent to which they felt they had achieved the official learning outcome for our course, “Students critically analyze and communicate complex issues and ideas.” Not only were they unanimous in their verdict that they had increased their ability to see, and analyze, and communicate complex issues and ideas (and, certainly, the written work they produced following our class discussions and as end of semester revisions bore this out), but the students were also able to explain this achievement quite articulately, itself a signal of their triumph over the SLO. Their anonymous end of semester evaluations of the course overwhelmingly confirmed the value of our whole class discussions in the course toward developing their own critical thinking. bell hooks’ accessible, provocative, political, and enthralling work played an indispensable role in Fall 2022, as she had done 30 years earlier, in helping my students move from noting the obvious and repeating social platitudes to making unexpected arguments, critically interrogating received wisdom, and confronting dominant discourses and power structures, what hooks calls “dominator culture.” The ability of bell hooks’ work to open up these kinds of pedagogical spaces, and the engagements it elicits from my students is where I find the hope in desperate times.

Works Cited

Barnard, Ian. “Disciplining Queer.” borderlands e-journal, vol. 8, no. 3, 2009.

Birkenstein, Cathy, and Gerald Graff. They Say/I Say: The Moves That Matter in Academic Writing. 5th ed., Norton, 2021.

Boylorn, Robin M. “A Story and a Stereotype: An Angry and Strong Autoethnograpy.” Critical Autoethnography: Intersecting Cultural Identities in Everyday Life, edited by Robin M. Boylorn and Mark P. Orbe, 2nd ed., Routledge, 2021, pp. 188-202.

hooks, bell. Black Looks: Race and Representation. South End Press, 1992.

hooks, bell. Outlaw Culture: Resisting Representations. Routledge, 1994.

hooks, bell. Reel to Real: Race, Sex, and Class at the Movies. Routledge, 1996.

hooks, bell. Teaching Critical Thinking: Practical Wisdom. Routledge, 2010.